For most of us, studying abroad is the first time we experience how it is to truly live independently. Away from family, friends and familiar environment, in the first few months, without warning, I was immediately thrust into adulthood. Though not having had a year in, looking back, I find that it is quite ironic, that being a “newborn adult” meant that I had to re-learn commonplace stuff I knew back home and to go through life again as if a child:

- How do I get to who to knows where?

- When will I get my allowance?

- Where is my food? I am so hungry!

When I was still in the Islands (really, the Islands) with less than a month to go before my flight to Spain, I had imagined myself doing competitive research in well-equipped laboratories, rubbing elbows with big wigs, speaking Spanish, hablar con la gente—hacer amigos, amigas and having occasional trips to different postcard cities in Europe. I have not imagined a life of washing dishes, cleaning toilet bowls, cooking meals and carrying groceries—literally being a lone slave to an uptight Filipino-Chinese PhD student with no pay (well that is what a slave means). Now that I think about it, more than half of my time is spent on doing household chores than living the life I have imagined (barely at competitive and my elbow is still…unrubbed). I have completely not thought about the mundane aspects of living abroad.

How are other Filipino students in other European countries doing? In the 8-question survey I sent, we got 14 respondents; this is roughly 10% of the ORPHEUS. I don’t know the distribution of our members, but most of the respondents are from Central and Southern Europe: with Germany, Italy and Spain topping the list.

One of the drastic changes we experience living abroad is with regard to transportation. I have not been everywhere in Europe, but I think even the city with the worst public transport system would fare better than the horror that b ears forth the traffic in Metro Manila; walking is not even an option. Well we have the jeepneys (or in the vernacular, dyip) so we never have to walk—it’s only 7 pesos (10 cents)! And we can catch a ride and get off wherever we want. That and tricycles—which is already a luxury at around 40 cents. So back home, we never have to walk under the sun. (oooh, Europeans and the sun, that can be another article) This is a compromise of two things I think, we get the convenience of the jeep and tricycle at the expense of the reliability of a developed transportation system.

Around 60% of the respondents walk to work/uni while the rest use the bus or tram or a combination of all three. For now, I walk to the institute but come September I’ll be moving out of the dorm and I’ll be talking a bus and a train. I don’t mind this change in mode of transportation and I have to admit that I actually enjoy the commuting in Europe. Systems have a schedule, follow the schedule (most days) and are impersonal. Even if you don’t know the place you want to go to, you just need to look at the map of the routes and you can get there. There is also minimal human interaction and siksikan events are scarce—you don’t have to take to someone to buy tickets and bodily contacts are down to a minimum. But this comes at quite a cost; I know we should not convert but a single journey ticket in most places costs around 1 to 2 euros, that’s taxi price back home!

Things are more expensive here really. Although “expensive” is relative. In different places within EU, prices are different. From the survey, mean values of bottled water are cheaper in the Iberian peninsula than in Western-Central Europe. Actually, you can treat the survey question as a psychological test. I think most people really don’t know the price of a 500mL bottle of water in the grocery. Honestly, I just guessed (and my price was right on the dot of the mean in the Iberian Peninsula!). What is expensive is relative even within the same country. The price I gave was what I was willing to pay in the grocery and I suppose other people also did the same. In Germany I guess people are more varied with their attitudes towards prices, or maybe just towards water, or towards answering surveys or maybe I just can’t tell from 14 respondents! But from the trend, things are cheaper in Spain-Portugal than their neighbors.

In general, everyone (93%) receives money from a stipend or scholarship. I know the amounts are not fantastic, we get what we receive. But on the brighter side, this is the best time however to convert to peso! Nonetheless, even if a scholar’s pay is not the highest, more than half (57%) of the people are satisfied with what they get, only less than a third (29%) being not satisfied. But it is quite ironic that people in Western-Central Europe are more satisfied with their financial status even with higher expected costs of 500mL bottles of water, with only one respondent saying no—while in the Iberian peninsula, with cheaper water bottle price means, 3 out of the 4 respondents have a clearly negative answer as to their satisfaction with their financial status.

From the answers in the survey, one can project the stipend the respondent receives. (I just made the following equation up). I took the price of half a liter of water, multiplied it by some number to get base housing cost and multiplied that with housing type. Then I added grocery expenses and modulated that by frequency of cooking and eating out. All the expenses are then modulated further to get all expenditures. I used savings as a measure of satisfaction and projected what percentage of the stipend are used for expenditures. Kind of crazy huh. I guess all the economics majors here are flaring their noses now. But from this projection we can see that the range of the stipends people get is quite broad from 600 to 2700. Well I think this makes sense kind of because some people are here for short term stays and some are here for postdoc positions. The mean is around 1380 euros.

Financially, I try to cope with cooking ALL my meals. Almost everyone cooks in Europe (93% of respondents) and most certainly everyone studying here has had a hand in cooking at one time. I think we could really benefit from having a series on (CHEAP!) cooking at the ORPHEUS blog. I was wondering why there is no book out there yet on cheap, easy and delicious food which students can prepare with just a hotplate or a microwave! This would really sell, or maybe not, since the target audience would be a group of misers. I prepare all my food—my breakfast, lunch, dinner each with two plates and a dessert and 3 meriendas.

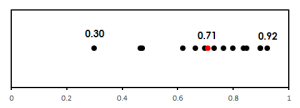

Six meals a day might be excessive but I think people are not eating enough in ORPHEUS. Again by projection—by taking the quotient of grocery expenses and the ratio of price of water and cooking frequency and getting the difference of the inverse of this from unity—we can gauge how well people are eating. We can set 0.7 as a level wherein a person can be said to be eating well. This is equivalent to cooking all meals with three meals a day with enough protein and veggies and then some or eating out all the time with just one plate, no drink. Talking about the mean, we eat well but that is not good. It means that some are really eating poorly—with some values going as low as 0.3 (cooking all meals for a month for less than 50 euros for a high cost of water). Come on guys, let’s eat properly or maybe the model is just messed up. Anyway, it was fun making graphs and models.

Living abroad made me realize that I really miss the comfort I had in the Philippines—from transportation, finances and food (OH THE FOOD). But this living abroad-living alone thing is kind of exciting but I think I have to take baby steps in each aspect of living abroad.

2 comments

Comments feed for this article

August 13, 2012 at 10:58 am

johannaindias

wala kasing random sidewalk vendor dito…street food = those you find in caravans / trailers and they aren’t exactly cheap. and we have…convenient stores which are open 24/7.

August 14, 2012 at 6:57 am

ilcapitano

here in Napoli (a much bigger city than Trento), we do have street food… fried pasta disks, rice balls (arancini) which you (David) love, bombolone (sugar-coated pastry creme-filled donuts) and they cost around 1-1.5€ (so pretty cheap).

and swerte mo, Shine, to have convenience stores na bukas 24/7!

[Good job btw David!]